- Home

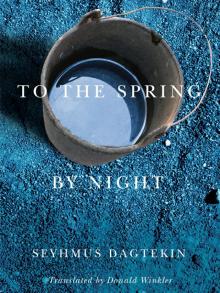

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

To the Spring, by Night Page 11

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 11

Majnûn loved Laylâ, his cousin. They had grown up together, tending their herds of goats near their tents. They had played together, with their goats or on the backs of their camels. They had drunk at the same oases, gazed on the same dunes. From stopping place to stopping place, they had crossed expanses of desert and mountains. Laylâ was beautiful, more beautiful than the gazelles that Majnûn spotted from time to time near his goats. And Majnûn was more beautiful than a bird in the sky. Their love was comparable to their beauty. The more they grew, the greater was their love. But Laylâ and Majnûn’s beauty and love had their enemies. And just as their love was about to flower in all its strength and beauty, the enemies became afraid, hatched a plot, and separated Laylâ and Majnûn. He was locked up with his goat and his camel, and she was led away with her family and her tribe. It became impossible for them to live their love on earth. As they were about to succumb to their enemies, god, in his compassion, brought them up to the sky, alive, one with the other. He took them from their enemies, so they could be reunited in the sky. And, at the end of time, under the peaceful reign of the Mahdi, god would bring them back down to earth so that their love would be consummated.

The two stars were separated, far from one another, each one brilliant in its own part of the sky. My mother told me they were waiting for the living to fall asleep before coming together, as they did every night. And if, as you fought off sleep, you were to surprise them in their union, they could make your wishes come true as long as you kept their secret. I told myself that if I ever managed to surprise them I would wish to live for a thousand years with my sweet cousin, the star of my heart, who would have become my wife.

I was already tending the goats, but my cousin, smaller than me, didn’t do so yet. We were not the same age, as Laylâ and Majnûn were. But in a few years we would be able to tend the goats together just like them, near the village. Knowing the territory and a few secrets about goats and other things, I would teach them to her in my turn. I had only seen gazelles from very far away, but that was enough to persuade me of their beauty. My cousin was beautiful also, with a beauty that would not take long to flower. And we would perhaps come upon some gazelles and gaze at them together. This love deep in my heart had no enemies. And so I was going to ask to live a thousand years of happiness with my cousin, who would be my wife.

But the evenings were short, the nights were short, and sleep was heavy and long. Laylâ and Majnûn each stayed on their own side of the starry sky of my childhood nights. And my cousin remained under these stars, deprived of the antelopes that inhabited my childhood gaze.

Yes, the known world was the terraces, the fence below the terraces that encircled the resting place of the goats and the horse, mingling their ruminations and mastications with our sleep, and interweaving their waking lives with our dreams. Then there was the slope below the fences, up to the borders of the cemetery, an empty space. The empty space that I overflew in my airiest dreams, and filled with multicoloured marbles in those dreams brimming with incident. The empty space inhabited by the dead, in the centre of which rose the tomb of Hâji Mouss, the guardian of this space opposite our house, and guardian of all it contained.

Hâji Mouss was the patron saint of orphans and of old people lost in the fog or the gloom of night, for whom he lit a candle to guide them to a safe haven. He was also the patron saint of the vines, and of the goats, and protected them from thieves and wolves. He protected the wolf from the forest, the forest from fire, the fire from rain. He protected the tortoise, which we would hang by the neck to bring on the rain. He protected the ant that, wanting to cross the spring, risked falling into the water and drowning. He protected whoever held a branch over the spring like a bridge, to ease the crossing of the ants. He gave grass to the goats, milk to the shepherd. He was Hâji Mouss, reigning over the dead and the living in our land. A land blessed by the saint, the wolf, and the goat.

And so we felt that our herds, our forests, and our vines were protected from any ill will those around our village might bear them. For the possessions of some people might appear excessive, making others want to take them away. Some, rather than asking that everyone prosper together, might bring on the ruin of others along with their own, as we heard in the story of the poor man who, having no mount, asked god to give him a donkey. God told him that, if he asked for a mule for his neighbour, who already had a donkey, then he would be able to have a donkey. And the supplicant, horrified that the neighbour might then have a mule, replied that he would rather have no mount at all than give a mule to his neighbour. We didn’t have much in our hills, but the little we had could provoke jealousy, could lead to a hatred that we found difficult to understand, and that sometimes gave rise to extreme acts. Acts that had to contend with the vigilance of Hâji Mouss.

Those who wanted to damage a vineyard were pursued by the stakes that supported the vine stocks, as if a dozen invisible hands were wielding them to chase the culprits from the vineyard. Others, seeking vengeance for a dispute between our two villages, wanted to cut down a part of our forest during the night. With every blow inflicted on the tree, their tools were damaged rather than the tree. Still others stole a goat from the herd and led it away to cut its throat in the caves on a neighbouring village’s land. They lit a fire and put the meat on a large platter. During the night they fried up the meat and, once it was cooked, they doused the fire, planning to rest so that they could better enjoy the feast that awaited them. When they awoke, the meat had been transformed into filth.

Confounded, on the following days they came with profuse apologies to confess their misdeeds and misadventures. They brought offerings and food to Hâji Mouss’s tomb and asked his forgiveness. By the end of the visit the disputes were settled, hatred and animosity had disappeared, and there were no more such initiatives for a very long time. And Hâji Mouss continued to watch over the land and those who came to him for protection.

But sometimes the villagers themselves turned on each other and did spiteful things. In such cases, the saint did not intervene, but let those who considered themselves his children resolve their differences on their own. Differences that could lead to insults, shouting, stones aimed at the head of an adversary. At other times things could become more serious, going so far as the destruction of plantings and crops and even vineyards, all during the night, of course. To speak of night is to speak of a veil cast over an act committed, to speak of uncertainty and ignorance. And ignorance was unbearable, especially when it was a matter of knowing who had set fire to a field of grain at harvest time, who might have gone so far as to raze a vineyard. Night was mute, the authors of the act kept their lips sealed, of course, and Hâji Mouss did nothing either. The wrongdoers must have belonged to the village. But how to know, how not to wound one’s neighbour or one’s neighbour’s neighbour with wrongful accusations?

One day, it happened to our vineyard. While we were doing our daily inspection, we found a good half of our vines cut down to the ground. What anguish, what misery for the hands, the feet, the eyes that had for so long worked to raise them up, to bring them to maturity, so that they would at last be filled with pride for the grapes they were going to bear! The fruits of five years of labour lay there, despondent. They had lost their self-respect, their freshness, they were green no more.

And we had no one to suspect. No recent differences or animosities. We reviewed the entire village, all the possible offenders, but could decide on no one. Nor could we bear this uncertainty. It was as if placing a head on the arms and shoulders that had struck down our vines, a face on the head and a name on the face, would ease the pain we felt. That same night, other vineyards had been razed. Above all, that of a great-cousin who had no more reason than we did to fear such an act. He was as much in the dark as we were and wanted to find out who could have done something so disgraceful.

He had heard about a man in a village far off on the plain, a man who with his science could unmask those evildoers, those rats in the nigh

t. He discussed it with my father, and they agreed to go and see him. My older brother left for this village with the cousin. After a day’s walk, with everything it entailed, they arrived at the village, found the man in question, and explained the situation. The man told them they should have come with a child who was no more than seven or eight years old, and knew the villagers and the area. My brother was too old for the exercise to succeed. But seeing that he knew how to read and write, they agreed that he should note down the necessary formulas and prayers. The cousin and my brother came back from their trip, not with the criminal unmasked, but with invocations and prayers for my brother to recite at home that would achieve the same end. He immediately set things in motion.

The child who was going to participate in the experiment had to have reached the age of reason, had to be able to distinguish good from evil, but could not be spiteful in any way. His thoughts could not be tainted or led astray by wickedness, and he had to be close to innocence, open to wisdom. You could not go looking far and wide for such a child. There was a confidentiality to the operation that had to be respected. We could not arouse suspicions in our search for the guilty party. And so my big brother resorted to his two younger brothers.

I must have been six or seven years old, and my other brother, eight or nine. One was close to the minimum age, the other to the maximum. My brother went first. He was able to identify the places, to make out a few silhouettes to which he put names that seemed plausible to the grownups, my father and cousin. Then it was up to me to see if my brother’s visions needed to be modified in any way.

My older brother had made notes on how things should unfold, and he followed the procedure to the letter. It’s true that at the age of sixteen or seventeen he had been taught by a schoolmaster who had spent a few years in our village. He had then served a serious apprenticeship with a carpenter uncle who had some notions of reading, and some learning to pass on to him. And so he invested his role with the diligence and conscientiousness required.

He began with some recitations in a low voice, and then smeared black ink onto our right thumbnails. He began to chant his invocations and his prayers, during which time we had to stare at our thumbs, which were now windows open onto the night. It was as if our ink-smeared nails had become dark transparencies through which we could revisit the night when those acts took place, as if the veil that had covered those abominations had been drawn aside. I listened to the voice of my brother as I stared at my black polished nail. I saw the terrace, its full length covered in branches that were undulating in the wind. I saw trees, perhaps pistachios. I saw silhouettes moving near a wall that formed an angle with another. I saw the silhouettes approaching a thorny tree that looked as if it was about to fall on their heads. I saw footprints through the undulating branches. I saw scythes releasing into the wind branches that flew off with their grapes like so many heads coming out of my thumbnail. I kept staring at my nail, but didn’t know what to say. I had never travelled far from the village, and what I saw was unrecognizable and strange. I could not situate the cliffs; nor the terrace, nor the branches, nor the silhouettes. I babbled a few words that in no way enlightened the grownups, who tried to understand, to puzzle out what I was saying to them, while my brother continued his invocations and brought the séance to a close.

A few years later, when I was becoming more familiar with what lay beyond the village, when my fear of these once imaginary geographies was being supplanted in my mind and before my eyes by real rocks, cliffs, and trees, then these once-wavering visions began to steady themselves and become more concrete. And it was during one of these outings, while I was leading our horse to pasture, that I found myself face to face with the vision of my thumbnail. Everything became clear, like a picture unveiled. Everything was in its place. The terrace, the cliffs, the vines with their undulating branches, and lower down, the young pistachio shoots, indeed razed to the ground some years earlier, when I had my vision. But the known world was still hidden by a veil that would not part for years, until the time when I would comb through the cemetery, with its graves, and the saint’s domain.

Beyond the domain of the saint and the cemetery, the known world ran on, rose to the height of the citadel, and from there plunged downward, this time falling into an invisible void on the citadel’s far side, looking off to the villages on the plain. An endless plain, so they said. A plain upon which you could walk for entire days without finding rocks or woods or forest, and certainly not mountains, a plain that was cultivated over its entire expanse. There was wheat and barley everywhere. We understood then why our donkeys went down to the villages on the plain when they wandered off. Later we would learn, we would discover that this was not the only reason; there were also she-asses in abundance that attracted our donkeys, unlike in our village, where there were none. But for the moment the wheat and barley seemed to us to be reason enough.

The citadel, acting as a boundary, shielded us from this expanse. From afar, it loomed on the horizon like the end of the world, the one that was known to us and that we could take in at a glance, the world of our village. For a long time I thought my head would touch the sky, especially the clouds, if I scaled the citadel. The grey clouds, engorged with rain, bore down on our dwellings from the heights of the citadel, or else hung there, unable to advance. Clouds that with their rumbling and their flashes of lightning over the citadel called up echoes of other lives that must have run their course on those heights in distant times, we would be told later. The known world had its limits.

On fine days, when the clouds were high and completely white, the limits that were not fixed for all time receded. And on those days we saw airplanes pass over like enormous, noisy, high-flying birds. We were afraid of them. Because we knew that birds smaller than those called planes made off with snakes, chickens, and even lambs. Sometimes parents feared for their children because of these birds. And sometimes the planes flew so low, with such a roar, that we abandoned our games to scatter and seek refuge under a tree, a rock, or in the arms of the grownups. At other times they glided very high up, slowly, and their muffled sound barely reached our ears. It became a pleasure to observe them, like the flight of a bird in a windless sky. On those days they disappeared into the white clouds, and reappeared farther on. I believed that these planes, flying high and slow, loaded themselves up with cotton as they crossed the fluffy sky, and brought it down to earth. The white of the clouds against the blue immensity of sky was like the cotton on the bright red of our sheets. One calmed our gaze and inspired our infinite imaginings, the other ushered us into the night and sweetened our sleep. One was the horizon that prolonged our waking dreams, the other the cradle that embraced our dreams at night. This whiteness of cotton could not, I thought, be of the earth. It must have descended from the whiteness of the clouds above our heads. And this thought united our mattresses and our eiderdowns with the clouds in the sky, in the wake of the planes that flew over our village.

The backs of the houses, the back of the village, faced north, and vacillated between the known and the unknown. The village was nestled on a rocky slope, the opacity of the rock shoring up bodies and houses the way the opacity of the night supports sleep. The darkness of the rooms at the back aroused uneasiness, just as the night brought uneasiness to our hearts. These rooms backing onto the rock were windowless, with an opening in the roof that served as both skylight and chimney. They were the repository for the houses’ yearly provisions and, in their coolness, for hidden memories.

They were easy to block, these openings. And when, as a prank, we wanted to smoke out a neighbour or an aunt who was baking bread or cooking inside on winter days – in summer cooking and bread-making were done on the terrace – we sat on the opening or blocked it with a board to keep the smoke from escaping. After two minutes the air became unbearable, suffocating. Depending on the mood of the moment, this provoked either hilarity or reprimands preceded by shouts and threats. Once the room was smoked in, we were happy; the reacti

on didn’t matter. We took flight before we could be identified. We could always own up later if we hadn’t already been identified by our noise and laughter. But times were not always good for the occupants of the rooms at the back. There was certainly heat in winter and coolness in summer, but these rooms could, at any time of the year, be places for the settling of scores, fits, convulsions, cries stifled by blows. They could be the site of blood, coagulated and hidden away, of cold bodies, of lives snuffed out.

It was in one of these rooms at the back that my young aunt by marriage hanged herself, or was hanged, we never knew exactly. It was said that she could not bear the betrayal of my uncle, who had become infatuated with a married woman. The married woman was very beautiful, certainly. Her husband was a good-for-nothing, a weakling, they said, and too young for marriage.

I only knew the husband after his military service. He had forgotten the language spoken in our part of the world, as happened to other men from the village while they were absent, without their even mastering the one spoken in the army. For the men of our village this was a military disservice.

For their two years of service, later one and a half, they were thrown, without any notion of the official language, into the harsh and unfamiliar army world. They were proud of having performed their duty, which made men of them, whereas up to then they had been looked on as greenhorns, as virgins. “First do the army!” some fathers admonished their sons, who were eager to taste of the good things in life, the most coveted being a woman next to them on a pillow. The precocious ones who had already enjoyed this privilege were impatient to get their service out of the way in order to enjoy it more fully. And so everyone was keen. Bring on the call-up! Let’s get the service over with! In order to finish earlier, some even went without leave, because if it was not used, the time was deducted at the end. And in a sense it was quickly over. Yet, at the age of sixty, or eighty, they still hadn’t stopped talking about the hardships and mistreatments they endured in the two unhappy years they spent in the army, even if two years doesn’t amount to much at the end of a life. Not much, perhaps, but it left them with stories to tell for the rest of their days. And it was rare that these stories reflected anything they could be proud of.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night