- Home

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

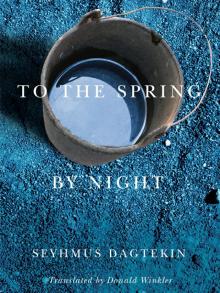

To the Spring, by Night Page 2

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 2

The thick walls, built of a double row of stones and a mortar of earth and straw, allowed the outside in and the inside out, within reason. Winter cold and summer heat were more tolerable within those walls, cocoons of wood, stone, and earth.

As far as anyone could remember, the village and its houses backed onto Mount Kêmêl to the north, backed onto it with such blind confidence that one could not, in the entire village, find a single window opening toward the mountain that blocked the icy winds of winter and let pass the cool breezes of summer. Not a single window, even to allow for the occasional fearful or admiring glance up toward the mountain. Not a peephole to ensure that it was still there, still holding the village close, keeping it safe with its solidity.

Mount Kêmêl anchored the village to its surroundings. It looked down on its environs as a ship’s mast looks down on its small world, as the upright letter of the first days lent support to the village and its inhabitants.

The houses had blind walls on their other two sides as well, east and west. At times they lined up, shoulder to shoulder, wall against wall, to the count of ten, making this uninterrupted succession of flat roofs a perfect playground for us in winter as well as in summer.

Beyond, there were the mountains. Beyond the walls, the village, and the forest, but before other villages on the plains or other mountainsides hidden from our view – so many mysteries, so many territories yet to be discovered – there were the mountains.

They surrounded the village and its lands, the houses and their rooftops; they encircled Mount Kêmêl as well, making it a tall ship poised on its heights, awaiting the floods.

A ship that we could leave only with difficulty, and then sparingly. Openings onto the outside were rare for this ship on the mountains, openings through which we could reach the plain that spread out below the village, offering us access to other heights. For the plain we had two openings, one to the southeast looking down on the fields some of the villagers tended there, fulfilling most of the village’s requirements for grain, and the other to the southwest, leading toward the town in the distance. A town, said the grownups, that was only the first inkling of other more remote towns to the east, and especially to the west, out of sight and beyond the distance we could travel on foot. Towns they had seen only during their military service, as far as the west was concerned, and during their perilous smuggling operations, in the case of the east and the south, and which they promised we would come to know when it was our turn to go off to the army or engage in contraband.

In both instances – in the southeast as in the west – the slope dipped just beyond the opening, making descent dangerous and climbing difficult, especially when the beasts of burden were loaded up with wood, cereals, straw, and dried leaves for the animals. When there was nothing to carry, the men, rather than walk, climbed onto the animals’ backs, sparing themselves for the work ahead in the woods and the fields.

The wood that was to be sold in town, and which, along with grapes, tobacco, and goats, constituted one of the principal sources of revenue for the villagers, needed to be carried by animals through the narrow opening on the west. This opening was so narrow that the villagers had honed their skills at loading into a fine art, piling up the beasts in such a way that they could fit through the gap without incident. In any case, everything was sold by load rather than by weight, and they were not going to burden their animals to death with wood they would sell for only a few cents more. It was different for the villagers from the plain who came up from time to time seeking wood. Since they made the trip only rarely, they exaggerated the load in order to take back in one fell swoop as much wood, as many branches and leaves, as possible. And on their return they had enormous difficulty trying to fit their animal through the opening with all they had piled onto its back.

One of those villagers from the plain so burdened his donkey with long branches that the poor animal, barely visible, advanced painfully, like a small hillock. As soon as it arrived at the passageway, the donkey’s owner became aware of the trouble ahead. He had imagined that the opening was wider, and only when he found himself before it with an overloaded donkey did he realize how narrow it really was. He wasn’t going to waste time lightening the burden, thus losing part of his precious load, or unloading it only to load it up again on the other side of the passage. Determined to preserve his advantage in terms of both time and load, he drove the donkey into the opening, but the poor animal, wedged in, could not go forward. He backed up and tried to retreat but, under the force of his master’s blows, he had to move into the opening once again. He still couldn’t make any progress. His master continued to assail him, and once again the donkey thrust himself forward with all his strength. He pulled at the saddle, at the load, but couldn’t widen the passage, even though he had the strength of a donkey. Frustrated in his endeavours, the master persevered and, more and more impatient, laid on blows wherever and however he could. While at first there had been a few jolts forward as a result of their combined efforts, the master now realized that for some time, despite his exertions, nothing had changed.

You had to shove to make a donkey move – that was well known – but now, even goaded, it didn’t budge. The man took a branch from the load to use as a club and give a well-deserved punishment to this lazy donkey that was making him work so hard, but it didn’t move an inch. He bent down, the better to see the donkey. To his astonishment, he was greeted by a gaping hole. No donkey. The load and the saddle were suspended in space. He hoisted himself up to see past the opening, and spotted his animal down below, free, descending toward the plain at a nonchalant pace, giving himself the luxury of a detour to the left or the right, to graze on whatever he found along the way. The man then realized that for some time he had only been beating the saddle, and only pushing the load. The girth had given way, and the donkey had escaped the saddle, the load, and the blows. He hadn’t been strong enough to widen the passage, and he was not about to move the mountain, which had been there long before his arrival. He was happy just to pass through by himself, leaving his master on his own behind the load. Here was one more trick that a donkey, out of desperation, had played on his master, a trick that his good nature, his self-denial, had played on the obstinacy of his masters and his detractors. His trick would become known, and his master would be mocked for his stupidity. But for all that, he would not be spared. The man was his master; he would find him, take him in hand once more and make him pass through the opening, whatever it took.

Here comes someone now, climbing toward the passage, hailing the master, taking the donkey by the rope and bringing him back. But they will always be there, the few mouthfuls of grass he was able to graze on his way down, the lightness and swiftness of his steps on the path, unburdened and free.

The grownups told us that this life was like a ship, that we boarded it and disembarked only by exercising restraint. No matter if the mountains were thick with wood, branches, and leaves; we could only load what our donkey could carry and fit through the narrow pass that opened onto the high seas of the plain. With a horse, a bit taller and a bit stronger, we could perhaps take a few logs or a few branches more, but even then we were limited by the horse’s strength and by the width of the passage, which was always the same, even though toward the top it broadened slightly to enable the horse to take advantage of his size and his strength, both superior to those of the donkey. Our desires did not determine the size of the opening, and it was in our own interest to moderate them, given the narrowness of the passage and the limitations of our mounts.

Our village, they told us, was made in the image of a ship, a ship that was the image of life.

Like a ship on the heights, our village kept us secure from the waves that swept off the plain and died out at the foot of our mountains. And beyond its confines, it made itself and its holdings accessible only within limits. Not all could enter, not all could leave. And we had to pay more attention to what came in than to what went out, the descent being more

easily assured than the climb back up. Even so, the ease of the one and the difficulty of the other could vary, depending on the traveller. The tortoise preferred the climb to the descent, when it was not too steep, while the hedgehog, which could roll itself into a ball and cushion itself, thanks to its resilience and its spines, likely favoured the downward path. And water was never more at ease, never more joyous than in the most violent descents, whereas it stagnated and sulked as soon as it went slack, and lost its way when it came to a flat expanse. Whether climbing up or down, coming in or going out, if we did not exercise moderation the passage was closed to us, the donkey abandoned us and, so the grownups told us, we were left with our burden, marooned there in front of the passage.

Our village was a ship and we the oblivious passengers, novices in knowledge and in consciousness, preoccupied with our ever-growing appetites and by our games which, at each step and at every turn, wilfully urged us to overstep all bounds.

Like our houses, each of the springs in different parts of the village had its own reputation, its own character. One was supposed to be good for tea because its water was not chalky, another was more pleasant to drink from, and a third was said to have water that was thick.

That spring, the one with the thick water, which was separated from the cemetery only by a slope and a field that was once a vineyard, was said to be frequently visited by djinns, those good genies and demons that shared the countryside with us.

Each spring had its own times, its own moments, with the djinns, we were told, perhaps to temper our fears with ancestral knowledge so that we would not carry them around with us like stones in our bellies; or so that our fears would be dispersed over a multitude of springs, thus lightening our burden. Or perhaps, supposing a malice that was just as ancestral, it was so that we would encounter our fears wherever we went: so we could go nowhere without them and they would always be there, some in our bags, some in our gut, some in our legs, some in our heads. And we would have no way to escape our fears.

We also learned that djinns did not like mingling with human beings in large numbers. They preferred to meet them alone or in small groups. Certainly, people ventured out elsewhere than to springs, but springs were, night and day, their preferred destinations, their most frequent stopping points. And djinns chose the springs to satisfy their longing to keep company with humans, or to fulfil their goal of harming them. Because there were all sorts of djinns, just as there were all sorts of humans.

Some didn’t like men, while others wanted to protect them from their malevolent fellows. The Creator had created djinns first, we were told, before he created humans. That gave them a kind of pre-eminence, making them our big brothers, and endowing them with a birthright that was not always defended or honoured in these parts. Among us, it even happened that the youngest, the junior, was favoured in the division of labour, and later, possessions. But that was another story, a story only concerning humans who paid little attention to djinns. The djinns insisted that the Creator recognize their rights. And that was none of our business. But it didn’t mean we were spared the complications arising from this demand. The Creator, in addition to granting them seniority, had created the djinns from fire, we were told. And the djinns lived in the state of adoration for which they had been conceived, until the day when the Creator told them that he was going to send a new species down to earth. A species that would worship him even when exposed to temptation, he told them.

“Is our adoration of you so wanting, that you should create a species that’s going to spill blood and sow discord on earth?” the djinns and the angels retorted.

The Creator replied: “I know what you do not know.”

He created man out of clay and breathed his spirit into him. He then presented him to the angels and the djinns. The angels saw in man yet another sign of the Creator’s goodness. The djinns were divided. Some agreed with the angels, while some were hostile to the Creator’s work, and vowed to thwart it for all eternity. Made from fire, they considered themselves superior to man, who was only made of lowly clay.

As of that day, while man was created only to bear witness to divine grandeur and to live worshipfully, the rebel djinns swore their animosity, and promised his destruction by any means, the grownups told us. Man, created to live on intimate terms with the divine, would turn away from the Creator. The djinns wanted to show that in men temptation would trump adoration. Pride blinded them. They disparaged the Creator’s work, and dedicated themselves, at great risk, to disclosing his errors: man would not persevere in the path of worship. From now on that was their gamble, that was their goal. They asked the Creator for the time and the power to compromise his new work, in order to achieve their ends. The Creator granted their wish, and gave them the power and the time to do what they would with man, while assuring them that man would remain worshipful, whatever they did to lead him astray. From then on some djinns were to be avoided, the grownups told us. But we didn’t know quite how to do it. Especially when it was a matter of eluding them at the springs.

We had no idea why this particular spring had more djinns than the others, and when we asked the question, the grown-ups didn’t seem to know either. We didn’t know if it was the thickness of its water or its nearness to the cemetery that drew them there more than elsewhere. But we did know that it was the spring most visited at the djinns’ preferred hours. And in practice, that was enough for us.

It was the spring to which men and women hastened as soon as they awoke at dawn, on their way to the fields. And which they passed when, at dusk or later, they returned, exhausted by a day of hard labour. It was the spring where all roads met, roads that led the flocks to the most distant pastures and the villagers to their vineyards, to their fig trees. It was full of djinns, they told us, this spring facing the cemetery, next to an ancient vineyard in which, even in summer, a few surviving stocks added green patches to the field here and there. As for us, we had our hands and heads full of djinns, abuzz with their stories every time we had to pass the spring after sunset or before sunrise. But that too is another story. A night-time story.

In the meantime, we tried to take into account the reputation of a spring when we were asked to fetch water. Our direction was determined by the way the water would be used. And we observed with wonderment that these springs warmed the water in cold weather, and cooled it in midsummer, much like the insides of our houses, which remained cool in the fierce summer heat, and warm when the winter assailed us with its ice and snow.

The resemblance between the springs and our houses went beyond the shift in seasonal temperature. There was another similarity, one more intimate, which linked water to man, given the respective dwelling places they occupied and passed through.

Most of the time, the springs had a large open-air basin, a smaller inner basin, covered over, and a dark chamber deep within, from which the water issued. The large basin was for the animals, the small one for humans. As for the dark chamber, it was the spring’s secret place where its mystery dwelt. We were rarely allowed to enter the inner rooms of springs; nor those of houses, at least not those of others.

When, for one reason or another, the village men uncovered this hidden part of the spring, we all gathered round to see the spring in its nakedness. We approached it with fear and fascination, and gazed on it as one would examine the entrails of a sacrificed beast. With the spring, the fascination did not last for long, even if the fear endured. We saw that it was just a trickle of water flowing from an opening in the earth or a rock, and that it was covered only to keep the water clean and not to waste it. And we saw that it was the same water, the same earth, both within and without. But seeing this and knowing it were not enough. Our eyes could not replace what we saw in our imagination with the clear picture we had in front of us; our powers of reason could not undo the stories about water and springs that stayed with us, asleep or awake.

And as soon as it was covered over again, the spring regained its sense of mystery. The curtai

n fell, turning this inner room into something impenetrable, and it became the threshold and point of departure for all our stories and everything we imagined.

Just like the springs, the houses had a part that was open to the sky and was used by people and animals in common, a covered section serving as a stable on the ground floor, with bedrooms one flight up, and an inner space at the back, a shadowy repository for the secrets and mysteries of the household. But that story must wait for the half-light of day or the dark of the night, the proper moment for stepping over the threshold.

As for the dark chambers, it was said that every spring had its own monster, and that on hearing the noise of the crowds, of the picks and shovels, it fled the spring or disappeared more deeply into it, to protect itself from the human gaze. Because the monster was selective about its appearances, it chose the times when it would make itself visible; it did not like being taken unawares. That is why we never saw it while the spring was being uncovered. It was described as a great snake, a dragon that in times of drought drank the water of the spring, letting only a tiny part seep out for the needs of men and other thirsty creatures.

But where could he climb out or disappear, since we saw no hole in the spring other than the eye the water flowed through? And unless it foresaw the work to come and fled during the night, it could not reasonably make its escape through the opening in the spring while it was besieged on all sides. We were told that it climbed further back into the eye of the spring and, in climbing, closed the hole behind it. We told them to dig farther, to look for it. They told us that the more we advanced into the spring, the more it would climb up or down, depending on the flow of the water. There was no way of capturing it, or even glimpsing it, they said, and even if we did capture it, another one would soon take its place. We had to leave it alone, it was at home where it was, and we shouldn’t disturb it. We wouldn’t appreciate it either, if we were disturbed in our home. In short, it suited the grownups perfectly well not to have to go looking for the dragon, not to have to confront it and reveal it to us. Having run out of arguments, we went silent, while they carried on with their work and left us still wondering. And the dragon continued to go back and forth in our heads between the earth and the dark chamber of the spring.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night