- Home

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

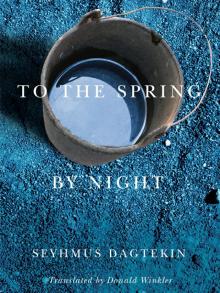

To the Spring, by Night Page 3

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 3

But during the hottest and driest periods of the year, the spring thinned out to no more than a dribble that took forever to fill even a pitcher, drop by drop. When we were desperately in need of water our mothers and sisters organized vigils, taking turns with other village women, with the djinns sometimes joining in. That was a story told, along with others, when the evenings became very long.

As for the monster at the spring, which was a snake or a dragon, we were told that sometimes, during the hottest part of the day, its favourite time and the hour when it would deliver up its prey, the monster, whose eyesight was poor but whose hearing was acute, would replace the trickle of water with a trickle of its poison whenever it heard a human approaching the spring. And at those times, when you came to the spring, you had to gather the first drops in the palm of your left hand, spill out the contents once your palm was full, gather a second handful in the palm of your right hand, bring it to your mouth, and drink only after you had prayed for divine protection from all the evil hidden from everyday human view. Otherwise, you would be paralyzed forever in the eye of the snake, or the claws of the dragon, and the monster would make short work of you.

How could our fear deal with an enormous snake, with a dragon in the chamber of the spring, which we had just seen with our own eyes? How could it, corpulent as it was, negotiate its comings and goings in earth that the men found so hard to excavate with their picks and shovels? In the parts of the spring open to view, the only living things we saw were leeches and worms. The worms were found mostly in the big basins where water accumulated and stagnated for a day or two before it went to irrigate the market gardens around each relatively abundant spring. The leeches lived mainly in the basins for animals and people, and they were the most dangerous things you could find around the springs. Once swallowed, they clung to the walls of our throats and filled up with blood until they stopped our breathing. We knew what would happen if we swallowed one. A grownup inspected our throat and pulled it out. But they were particularly dangerous for the animals that gulped them down in great numbers and had frequent coughing fits. Sometimes we understood and removed the leeches; at other times we thought the cough was caused by a straw that had gone down the wrong way, or the amount of dust in their food, and we waited for it to pass. But their bloodied mouths reminded us of the leeches, and now there was no mistaking. And so we pulled out the leeches, which had had time to grow as big as a thumb. It’s true that they were small and thin when they were in the spring, and could swim up and downstream as they wished. But even that didn’t make them monsters, and it was hard for us to imagine them as such.

But once the spring was uncovered, the dragon was gone, hidden from our eyes, and we saw no nest of leeches in the spring or in the earth. The monster would only return to take up its position in the spring and in our minds once things calmed down and order was restored.

How the devil did the dragon get into the hole? And if it wasn’t any larger than the opening, how could it have room for us in its belly? We had seen snakes swallow sparrows; we had even seen snakes swallow other snakes. But that a snake could swallow a human being and climb back into the spring with that weight in its belly without being noticed …? Our failure to understand did nothing to assuage our fear.

And there was always someone to tell us there was no problem, that everything was possible. If a camel could pass through the eye of a needle, a snake or a dragon – whichever – could work its way up the spring whatever the size of the opening, and it didn’t matter if it was in the rock or in the earth. It’s true that the grownups told us that if god wanted it so, a camel could pass through the eye of a needle without either one changing its size or its nature – that the passage would take place, the eye remaining an eye and the camel remaining a camel, just as they were. And so there was no point arguing about the size of the dragon, the victim, and the spring. And our lack of understanding wasn’t going to make the monster disappear from the spring. If we didn’t pay more attention, and ended up meeting it one day, it would be too late, but it would serve us right, they told us. And in any case, presented like that, there was no more question, no more doubt about the monster. It had to be there somewhere, and we had to keep it in mind as we moved about. We would not be able to force it out of its home. We had to live with its presence in the spring and in our minds.

The monster was diurnal, they told us, and the djinns nocturnal. The one showed itself in the midday heat; the others made their rounds between twilight and dawn. The monster stalked those who, trying to escape the heat, sought refuge near the freshness of a spring; the djinns attracted humans with fires and revels that made them visible at night. The one set out to lure us with the heat, and waited for us to approach the spring, drawn there by our thirst; the others wandered with their trappings through pockets of night, like nets into which the awaited victim would fall.

Their favourite season began in early summer and lasted until mid-autumn, until the end of the grape harvest. Midsummer, when some of the neighbourhood springs were bubbling over, inspired a number of celebrations. In mid-autumn, when the harvest was over, we let the vineyards prepare for their winter sleep, and the men retreated more and more into their homes. In the time between, everything was alive in the fields, on the roads, and around the springs; everything was festive. Springs of life and springs of fear, which we approached with hope and with apprehension.

Monster or djinn, both put in their appearance when, with our water depleted, along with the strength we’d had when we left the village, we had no choice but to stop at the spring. Times of thirst, times of return, and of hunger. After a morning spent in the fields with the grownups, chasing after goats in the pastures, we wanted to pause at the spring to quench our thirst and refresh ourselves. All the more so because we only began to make our way home once hunger, thirst, and the punishing heat of the sun were having their way with us at the approach of noon, or as dusk edged toward nightfall after the sun had set.

During the day the heat arrived early, after a short period of morning freshness. And the closer it came to noon, the more the atmosphere became stifling and heavy. The higher the sun climbed in the sky, the thirstier we were. All the animals and insects retreated into patches of shadow, under cover, so as to hold on as long as possible to the freshness and moisture that remained from the morning, the freshness and moisture that, in the shade of a leaf or a stone, they could steal away from the sun.

The silence, the stillness of noon, set in with its eternity of heat and thirst. Like the eternity of a drop of water making its way across our path toward the spring.

Most of the time, hidden from view by what had been built up around it, the spring only showed itself for the last few metres. These were not springs that offered themselves up to us, springs of joy and abundance that came to us of their own free will, as if by magic, to slake our thirst; on the contrary, they were springs that had been sought out, tracked down, brought to the surface by the force of will, by brute force, sweat, and pain. Springs that were dearly won and fiercely protected. Springs that tended to ebb beneath the heat, dwindling as we watched, and in extreme cases, to go dry during the mildest of droughts. Springs that we coddled, that we cherished, that we hid away from the most innocuous storm, that we placed under cover so that the first squall to come along, or a stray, malign bolt of lightning, would not snatch them from us. Springs that we guarded like the softest of our nights, that we greeted like the most joyous of our awakenings.

For the water did not willingly come to a halt on that slope where our village was to be found. Its instinct was to flow down to the valley, and irrigate the plains. And so, when we saw moisture that lingered through the summer, we understood that this water was trying to make up its mind between staying on the surface and running lower, and that we had to woo it with the height of our mountain, with love, with the devotion we could offer it whatever the season, summer or winter, spring or autumn. We would not let it get muddy, and we would protect

it from bushes, weeds, and animals. It would be for our tables first and foremost, for our buckets and our cooking pots. We would not let it trickle away like an ordinary stream: we would cherish it and treasure it. We would shield its source from the eyes of the curious and the shameless; we would shade it with a few cypresses, a few willows; we would cheer it with a few mulberry trees, and even a few fig trees, so that on the pretext of thirst, and sometimes going out of our way, our steps, large or small, would lead us there with greater joy and elation. We would give it a name and a legend, provide it with basins and surrounding land, so that it would refresh our fields and our hearts, so that it would enchant our dreams and our waking. Once it had been wooed, the grownups came with picks and shovels and began to dig, seeking water, seeking this elusive, ever-downward-flowing part of our selves.

But the more the hole grew, the more the wetness disappeared, the more the water mixed with the mud, and our sweat with the earth. It was a lost cause; neither song nor prayer could lure it to the surface, so we left it to a few earth worms that would perhaps get something from it before going in search of some other dampness in other holes. And yet sometimes we managed to unearth a trickle, a thin trickle of water. A trickle that would transform what at first was only dampness into a place of life, a place of fear.

After the digging of the hole and the capturing of the water, if the trickle was substantial enough, the building of the spring began three days later. At the spring’s birth, we sacrificed an animal with prayers and invocations, with a meal and a celebration, as we spilled into its flowing water the blood that kept us alive near where it stood. We made the sacrifice and let the waiting period pass. We agreed on the three days to be certain that the water had decided to stay with us, and so as not to build a spring we would later abandon. Because an abandoned spring was an unkept promise, a broken covenant, and could become a curse aimed at passersby in times to come. If the water was still there after three days, we began. The dark chamber, the little basin, the large basin. And then, later, the construction of the walls to contain the earth and its landslides. And far enough away to protect the spring from invasive roots, the planting of a few trees, a few fruit trees, especially a few mulberry trees. All that to make this place that was only wetness, then only a hole, welcoming to beasts and men. To transform it into a source of life.

This gave us springs recessed into the slope, hidden from view, out of range of passersby, springs that only showed themselves when we were present in body, and the body manifest in our gaze.

These recesses, which at the beginning and end of day sheltered the springs by offering them shade, became by midday, with their walls heated by the sun, furnaces that amplified the heat and the silence that surrounded them. The smallest sound disturbing the uniform background noise of the crickets’ song – crickets never seen, always heard, their song the furnace’s song, because it was loudest at those times – the smallest sound, or perhaps a lizard darting over a blazing hot stone, startled the passerby, who redoubled his vigilance as he approached the spring. Because it was hot, because we were thirsty, we were probably not alone in our thirst. There were likely others who were thirsty. Others, who tried as we did to overcome their fear of the spring and its daytime resident, and, as impatient as we were, also moved toward the spring, taking infinite precautions. That did not give us any more courage or make our approach any easier. On the contrary, it made our steps all the more leaden, our thirst all the more oppressive, in the midday furnace. At this boiling point of the day, parched, the mysterious denizen of the spring’s dark chamber – the dragon our fear situated in its eye – had already reached the spring’s outer basin to slake its thirst at the water issuing from it, and would have liked at the same time to make a meal of the first comer, man or beast, before retiring into its coolness for the rest of the day – even for several days. Until, its victim once digested, a renewed hunger and thirst drove it out of its dwelling place again to seek new prey.

Sometimes we dared not confront this fear. To the devil with the dragon, the spring, and its water! No matter how great our thirst and our desire for what was cool! We had held out this long and would hold out a little longer, and we would not expose ourselves to the jaws of that vile beast. Let it devour the earth where it lived, let it drink the water of its spring! With fear in our belly, we didn’t need its water. And let it see that we could do without! And so we chose to bypass it all – the devil, the dragon, and the fear – to go and quench our thirst at home, with the water our mothers had already spirited away from under the scrutiny of the spring and its denizen.

But we knew that the next day we would face the same dilemma and that we could not make the same detour. We knew we would have to accept the spring’s challenge if we wanted to grow in our own eyes and in the eyes of our mothers, who in any case were going to make off with its water.

Like the springs that flowed south, the windows of the houses also opened to the south, facing the sun. They opened onto sparrows, swallows, doves, at play or in distress. They closed to wind and rain, to fear and storms. It was at these windows that the storm unleashed its wrath, that the snowflakes came to perform their dance, that the sparrow and the dove sang their melodies.

Every flake of snow, every drop of water, and even every hailstone was, in its descent to earth, said to be accompanied by an angel. Otherwise, the drops would join together and fall from the sky not as rain but as sheets of water like entire lakes, and would drown the forests and fields, killing off men, flocks, and everything alive. Instead of beautiful, fragile snowflakes, there would fall mountains of snow that would suffocate houses, terraces, and villages; and instead of hailstones, blocks of ice would fall that would smash everything in their path. No man, no beast, no house on earth, we were told, would survive.

And so, to avoid such disasters and to maintain a certain degree of calm for the earth and its inhabitants, who considered themselves burdened enough in their passage through life and never ceased complaining on the slightest pretext to any ear within hailing distance – and so as not to add cares to their cares, or compound their adversity all along this journey – the angels joined in the descent of these celestial substances to earth.

They partnered in the dance of snowflakes before our eyes, they brought drops of rain down on our hair, on our faces, into the eyes of our goats, onto the manes of our horses. They lashed the walls and windows with sleet and drowned the fields with rain to keep our minds alive to the disaster that might ensue if they, the angels, were not there to guard against the anger, the moods, and the excesses of the water. The water which, if it was unhappy in its descent, could inflict a summary punishment on everything below, indifferent to the chaos and complaints it caused. For, in falling, it might want to push deeper, even deeper than the earth on which it fell. But no, the angels were there, and thanks to their watchfulness the water fell like a blessing, a source of life for our journey. Because, they told us, no heaven-dweller left home of its own free will.

From wonderment or fright, we remained glued to the windows in the face of nature’s outbursts, the extravagances of the water, priming ourselves to deal with other outbursts, other extravagances that would stir up the waters simmering within us, when the time came.

It was also through the windows that the sun shone in, to make the dust dance in its rays. The sudden appearance of dust in the interior sunlight was always a mystery to us. We couldn’t understand where these tiny specks came from, given that the room had been empty before the sun was there. Empty and pristine, especially since our mothers and sisters had just cleaned the house from top to bottom. They had shaken out the cushions, the eiderdowns, and the carpets, swept the earthen floor; they had dusted the glassware, the place settings and saucers, the picture frames, furniture and trunks, the decorative objects in the house. The room should have been empty and clean because what might have been dirt had been removed. But we didn’t realize that this cleaning process had stirred up an army of dust parti

cles that remained invisible when there was no sun. And once the dust was set in motion, all it took was a sunbeam to make the room full and lived in, to populate it with dust particles as numerous as the stars in a summer sky. The stars were now within arm’s reach, at eye level. We didn’t even have to raise our eyes to see them. They were there, all around, bearing us up, enveloping us. It just took one ray to bring their soothing presence to light.

One ray of sunlight, and we were no longer alone in the room, but in the presence of thousands of little beings, an infinity of tiny specks.

Dust dancing with dreamlike slowness. We blew air into the path of the beam and the dance became a whirlwind. A swirl of so many dust motes that it made our heads swim. A dance of dust giddy from our breath and the light. A Milky Way of dust wheeling about us, gathering force, wilder and wilder. We tried to calm them, but in vain. Every gesture we made lent more energy to their dance, brought more specks of dust into the beam. Those already there invited others, and they all swept us up in their movement. They wouldn’t stop, but kept turning more and more quickly. Tireless, they wanted no rest.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night