- Home

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

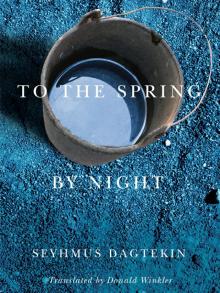

To the Spring, by Night Page 7

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 7

The east and its woods, over which day dawned and from which night swept over us. God in his infinite wisdom, we were told, wanted the east to be both the source of light and the source of the dark, just as the sun in its majesty was beset by weaknesses, so that no being might think itself intrinsically eternal. So that no arrogance might show itself in beings or in things. And so night swept over us from the east, from which came the light. In the half-light of dusk, the wind in the leaves, which cooled us during the day, became the trembling and whispering of countless invisible beasts, filling us with fear. The trees in the woods were transformed into giant beings, phantoms from another world that, barely glimpsed, set the innermost recesses of our small selves to trembling.

We took our courage in both hands to go and make sure that these were still the same trees as moments ago, that between our two glances no horn of the archangel Israfil, he who would herald the Apocalypse and the Resurrection, had sounded the end of any world, that no tortoise had crushed the eggs of any ant, that no serpent had swallowed any sparrow along with its babies in its nest, that no spider had caught any ladybug in its web, and that the world was still the world to which we had last awakened. We concluded: nothing had changed; the trees we were touching were the same as those of a moment ago, the grasses were in their place, and the earth did not betray our feet as we walked. But the trees a bit farther off were still threatening, and the house, too, began to seem unsettling, the more we distanced ourselves from it. We rushed back to the house before being stricken by fear or being questioned by our parents, wondering where we had been, if they noticed our absence. And it took only a few steps before we found the house as it was when we left it, and before the trees, once we had turned our backs on them, took on their ghostly appearance again, donning the apparel our fear had clothed them in for the night.

And so we avoided the end of the terrace that drew our feet, and in large part our minds, into the unknown, preferring to huddle up against the known, turning toward the neighbouring houses and the village whose familiar noises might ward off the silence and the menace of night in the east.

We were not the only ones to dread the night. The birds in the trees were no happier than we were when it arrived. They who, at the dawn of day, filled our mornings with their many songs, withdrew at the first sign of dusk into a painful silence that only increased our fear. To see them curl themselves into a ball as if they wanted to shrink their skin, to see them bury their heads in their bodies, their bodies in their feet, their feet in the heads of their little ones – to see them crouch down in their nests or in their shelters – you would have thought they were bracing themselves for the worst of disasters. The slightest movement, the smallest noise, made them jump, drove them even deeper into their bodies. As though they wanted to disappear from the night, to remove themselves from life. As though the gates of the night were gates of despair, gates of nothingness that they tried to avoid by clinging to their branch and their nest. You would have thought they were living every night as if it were their last, as if they were about to close their eyes to life, as if it were the last night of time.

But at the first hint of dawn, they began to wake us with songs as joyous as the day before, as if nothing had happened, as if there had been no fear, as if they wanted to pull down a shade of forgetfulness over our night and their own. But in the meantime we felt their fear, their fear stayed with us through the night.

To have one foot in the unknown in the east, itself plunged into the nocturnal unknown, was too much for our childish minds half-overcome by the night, busy reliving the day’s failures in the uncertainty of dreams to come. As our short summer evenings came to an end and we were preparing for sleep, we preferred to set up our beds right in the middle of the terrace, surrounded by other beds, in the known world far from the birds’ fears and the rumblings in the woods, and under the watchful eyes of our big brothers and big sisters. Mother and father guarded both sides, east and west, like markers setting our terrace apart from the unknown. And so it was nest-like, this gathering of beds in the night.

When my father was absent and my mother off milking the goats in the summer pen the shepherds had built for the herd outside the village, and when at night, alone, I had to watch the house until they returned, I sat on the west side of the terrace facing the village, so that I could share the company, even if it was distant, of the other inhabitants, listening intently for what might be going on behind my back to the east. To distract and calm myself as I waited, I kept my eyes on the comings and goings of the neighbours. These were times when we felt the unknown was breathing down our necks, while the known took shelter in the pupils of our eyes, with only the brightness of the moon and the multitude of stars giving us any comfort.

How could a far-off presence be any sort of match for this rush of fear? What could I do, who could I call for help, and what use could our distant neighbours be, all of them busy with their plans for this night and the following day, if without warning I found my neck between the jaws of one of the monsters I imagined hidden behind the trees, in the wood to the east? And what could the birds do, huddled together in their nests under the roofs of our houses, in the branches of the mulberry or the almond tree, except to fly off into the dark, far from the frail protection of a nest in the night. It was a vain hope to turn toward the village or align ourselves with the birds, who themselves were seeking a hollow where they might shelter their heads and bodies from this fear. But it was a hope to which I clung, a hope that sustained me until my mother returned.

Terraces and village, woods and mountain, all blended together, and no distinction was evident when, come winter, the village, the fields, the forest, and the mountains were covered in snow and formed one whiteness, dark and cold when it was cloudy, and blindingly bright when the sun shone. During the day, everything opened up to us. We found ourselves on a white expanse that went on forever. Everything was an extension of the terraces, and presented infinite possibilities for games and races across this whiteness that burned our eyes, that took away our breath. But it was then that the fear, creeping out of the woods and the trees to the east of the house, came right to our doors, and was no longer a function of the trees in the night, but was now audible in the whistling of the wind, visible in the tracks we found in the morning on the terraces, the roofs, and around the houses, and which we took – not without reason – to be those of the wolf.

Night fell quickly, even if the whiteness of the snow delayed its arrival. Even if there were times when the night could not hold sway. Because the brightness of the sky, the dominance of the moon, the whiteness of the snow upon the earth, held the edge of night at a distance, and kept it from sweeping over the earth, over our land. Evening came quickly, night fell even more quickly, when the sky was clouded and the moon was concealed behind a grey sky suspended just over our chimneys. We hardly dared leave our houses or expose our bodies to the uncertainties of night, even just to relieve ourselves, to ease the weight that nature had imposed while night and snow were crowding our walls.

Our mothers took us by the hand and gave us the courage to attend to our needs while confronting the fear that lay in wait for us outside. We emerged into a silence punctuated by a few barks and the occasional howl that lent a deep uneasiness to the night’s peace and its uniform whiteness. There was something in the distance that we sensed but could not fathom, something we strained our ears for, as if listening for doors opening, rifts in the night.

We saw that breaches could be opened in the night, that it was not an opaque orb of trembling and fear, that a kind of serenity could make its way in and find a place for itself there. We could share in this serenity and taste of it, even in response to the needs of nature, and the night could become a realm to explore, which would reveal to us, differently, all the beings and objects around us. But just as the bird and the goat were not fooled by this calm, and sought refuge as soon as night fell, we were not taken in by the silence, by this peace, which might

at any time turn to menace. Before we could come to know all there was of the night, fear caught up with us with a whistling of wind or a crackling of snow, and threw us back on our initial uneasiness.

These nocturnal outings were an ordeal for our mothers, who tried not to make us aware of their own fears. Our mothers who, because they were said to attract wolves at night, tried to hide their natural scents under enormous shawls. They tried to conceal them to protect themselves and to protect us from the curse of what was spoken of – things that could befall us in the blink of an eye, and which heightened the fear in every step our mothers made. Steps that heightened the fear in our hearts. Fear they navigated in the night and in the snow, by the flickering light of an oil lamp. Fear they tried to ward off with prayers and invocations or by camouflaging it in our own fear, holding tightly to our hands clutched in theirs.

As long as they were standing there, we always had the corner of a shawl to hide us behind our mothers’ fear, the fear that bound our flesh to theirs, that bore through our bloodstream every branch sighing in the wind, moving through the tiniest veinlets to the most secret recesses nourished by our blood. But as long as our mothers held us by the hand, as long as we could feel the rustling of their dresses at our side, the night could bestow on us a little of the peace we must have known within the womb. The peace that every seed must have known in its valley before being flung by the wind into the tumult of the heavens and the earth. As long as they held our hands, the night was an extension of their womb, and passed on to us a small part of this serenity.

As long as they held our hands, as long as they could keep our hands in theirs. Hoping they wouldn’t find their hands empty of the hands they had been holding. Because it happened that a mother returned home, her hands emptied of the hand of the child she had just led outside. That a simple visit to the outdoors prompted a return she could not have thought possible in the worst of her nightmares. A return filled with cries and lamentations, madness and despair, pleas for help, imploring heaven and earth, life and death, rousing the household, which roused the village, the birds, and the trees, disturbing everyone who slept and everyone awake. It was all very well for us to be accompanied by our mother, to hear her breathing above our heads, but still the fear never left us when such an event had taken place before we went forth.

It was during one of those cold nights, snowy and calm. One of those nights that have you trembling from fear or cold, you don’t know which, and keep everyone inside his shelter, in his nest, in his skin. A night that makes you regret the glass of water you drank or the extra morsel of bread you swallowed. But one does not choose one’s nights, one lives them.

It was on such a night that a mother in a nearby village had accompanied her little daughter into the snow, away from the house, so we learned one evening when we were told everything or overheard what was said. She had left her daughter just beside the house, behind the wall, so that she might return to bed with her body relieved, just as she often did, but a little later than on other nights. Or else the girl, awakened in the night, had asked her mother to accompany her outside. Having covered herself, she covered her daughter and led her out under a clear but moonless sky.

Just as the girl was seated and the sleepy mother was adjusting the sheet over her shoulders to protect her from the cold, a beast leapt out of the night, pounced on the little girl, and seized her by the arm. Taken by surprise, the mother rushed forward and grabbed the other arm, pulling with all her strength to free the girl from the jaws of the beast. For a time, each pulled on the arms of the girl, who, crying and struggling, tried to throw herself toward her mother. But the beast, more powerful, tore its prey from the mother’s arms and fled, while the voice of the child calling her mother for help continued to cry out. Shouting to awaken the household and the villagers, the mother began to chase the beast, pursuing the screams and the tears of her daughter as they became more and more distant, weaker and weaker.

Seeing that she was not going to catch them, she returned home to seek help, to send stronger, more agile legs and arms in search of the beast that held her little girl in its jaws. Awakened, the men of the house, soon joined by other villagers, looked for tracks, listened for cries, moans, growling, in the direction the mother indicated and on the surrounding land. They turned over branches and bushes, searched in hollows and around rocks, scoured embankments and shelters, but found nothing in the half-light of that icy night. They returned frozen and spent.

It was only the next day, at first light, that they discovered a scrap of bloodied cloth here, a tuft of hair on the snow there. And a few traces of blood.

That was all the mother could bring back of her daughter to the house the next day. That was all she could hold in her hands, against her breast. Her daughter, who had gone out in the night, holding her by the hand. Her daughter, who had left her hands empty, and her ears full of screams. That was all that remained of her: a bit of cloth, a tuft of hair, and her cries for help as the beast bore her away.

We too went out on cold and snowy nights, with the screams of this little girl in our ears.

When the evening was slow to come, and the night had difficulty spreading its black shawl over the sleeping houses and the souls it sheltered, given the triple conjunction of snow, sky, and moon, then it became something else – a full and mysterious brightness peopled by those wanderers in the absolute, the hunters, and the traces of the absolute, their prey, night watchers in their own right: partridges, hares, antelopes, foxes, jackals, and … the wolf. Deprived of the generous and abundant covering of night, all the wanderers lay in wait for a breath of deliverance or a fatal encounter, seeking a shred of flesh or a mouthful of food. All were watchful, some fearing others, some shying away from others, all feeling the breath of the hunter down the back of their necks, the breath of the void within their bodies, turning like the still point of the whirlwind. And in the glacial cold of that snowy expanse, loosed onto this white sheet by an inadequacy of the night, they went their rounds, circling our fear, circling the village.

Rounds so far-reaching that they sometimes prolonged them beyond the night, beyond the snow, and risked leaving their bodies behind them in the freezing cold. One of the great-granduncles, having left his body, contacted his wife in a dream, and the next day was found frozen on his rounds during a night of hunting. Frozen in place, his finger on the trigger, poised like a hunter awaiting his prey. It was not unusual to find prey frozen in the night, as if not to leave their hunter alone when he departed for other rounds under other skies. Because the grownups told us that under other skies each would awake to his passion, with companions who shared that passion and the thoughts that went with him on his way.

Opposite our house, in winter as in summer, was the tomb of Hâji Mouss, the patron saint of the village and its surroundings, the guardian of the living and the dead, the purveyor of hopes and fears – he through whom losses found consolation and joys a home, he who watched over the coming and going of every pious thought, of every impulse to goodness, who stood in the path of every malicious intent.

His tomb rose over the cemetery and the land around it. Land that inspired respect and fear, and that the most devout trod barefoot and bareheaded, approaching with prayers and invocations. It was visible from almost everywhere in the village, and you could call on it as a witness and appeal to its arbitration just by pointing to the tomb, inviting others to swear by the saint, even for the smallest disagreement: conflicts over the boundaries of fields and woods, differences as to the sharing of the harvest, and even disputes among the women when they could not agree on their place in the waiting line at the spring. Everyone could turn toward that land and its occupant, and find it within view. Our house was the closest to the saint’s tomb, the one that looked out on it, straight ahead, the one that could not turn away from it without being seen.

And so, if we always had an eye on Hâji Mouss, he always had an eye on us. When we were afraid, that was a comfort. At other ti

mes it became burdensome and unsettling to have the saint’s eye on us, and the eyes of the dead who surrounded him in the cemetery, each with stories and fears that compounded our dread when the names of the deceased returned in tales told by the grownups on long winter nights. Once we were bedded down for the night, the stories echoed in our minds, peopled by those presences in repose in front of our house, with the saint at their head. We had to wonder whether we were in our beds, or if the house had been taken over by the cemetery and those there at rest.

The grownups reassured us. The dead did not return. We could dream about them, but they stayed in their graves until they were called on to take leave of them. And for that you had to wait a long time; you had to wait for the end of the world. The dead were very occupied in their graves, and did not live at the same pace as the living. For a dead person the time of a life on earth lasted no longer than it took to sew on a button. As soon as they realized they were dead and would remain in their graves, they began another life, and had no more time to think about coming among us. Because in the beginning, a dead person did not know he was dead, they told us. When he saw that we were mourning someone who was dead, he too began to weep without knowing for whom. He too got busy preparing for the burial, for greeting the guests, and accepting their condolences. He too prayed and washed the body, and went with it to the cemetery, but wondering who it was. Once the body was lowered into the grave, he too helped to cover it with a row of stones starting at the head, and then to blanket it with earth. When all was finished and the assembly had left the cemetery, he too wanted to leave, but his head knocked against the first stone set down over him. He understood then that he himself was the deceased, and that he had just collaborated in his own burial. And so the dead did stay put in their graves. Still, their stories continued to trouble our thoughts, disturbing our sleep and our winter nights.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night