- Home

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

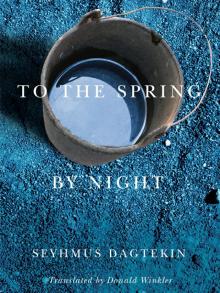

To the Spring, by Night Page 8

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 8

For winter was the season of death even if it was not the dead but their stories that frightened us. The season of death and hunger. During its tenure, the rain, the snow, the wind left us no greenery, except for the leafy branches of the evergreen oak that met the needs of our goats in winter, keeping the glossiness of its leaves and finding no taker other than the goats who, in their persistence, paid no attention to its thorns and gobbled them up by the mouthful. Everything else that might serve for food was, at the height of winter, blanketed with a uniform coating of snow hardened by wind and ice.

And everything was hungry, the herbivores, the carnivores and, from time to time, even man, this unscrupulous omnivore whose boundless appetite made everything tremble. Yes, even man sometimes went hungry, he who from beast to plant, from leaf to bark, filled his belly and made a meal of just about anything. But when there was no beast, or plant, or leaf, or bark, everyone was left with a hollow in his belly, a hollow that could bring in its wake the worst abuses, the worst debasements, sweeping away limits and barriers, shame or pride, love or goodness. “Lord, do not afflict us with hunger and dishonour” was one of the prayers we heard most often from the mouths of the grownups who had lived through the years of privation. A prayer that one sometimes heard uttered in a trembling, tearful voice, as though it led us to repeat this privation, as though it could bring it back. Everything was hungry, and everything sought some morsel of sweetness, a scanty subsistence, the barest crumb for the teeth to bite into and the intestines to pass along, anything that could first fill the cavity of the mouth and then that of the stomach. If only for a little respite, to allay the fear this emptiness spread through the rest of the body, so that they might to go off in search of new mouthfuls, and continue their journey on earth.

Hunger reigned, and when winter followed on a year of poor harvests, then there was famine and man had more than his share of it, relying on harvests as he did.

Famine was pre-ordained; it arrived like a fast, to the exact month, day, and hour, we were told. But we did not know its hour. One day, when one of our number was visiting a neighbouring village, he was privy to a conversation with the sage of that region, respected also in the surrounding villages. He announced at a small meeting that the famine would begin on a certain day at dusk. The man came back to the village, uneasy, but, as the sage had advised, he said nothing to anyone, wanting to promote a very moderate consumption of food. Consumption was already extremely frugal, the harvests having been meagre, but even with this small amount of consumption, given the remaining time, the man had to push even more for moderation. As dusk fell, a guest arrived, with his hunger. The family had already eaten and only the guest remained to be served. The villager took his wife aside and told her to mix one measure of flour with equal parts of ground-up goat hairs. The woman protested, because she wanted to receive the guest as generously as she could, and they still had some reserves. But as her husband insisted, she prepared the mixture he had asked for. And when she arrived with the baked bread and set it in front of the guest with a glass of water, to her great astonishment there was no reaction of surprise or disgust, but evident pleasure on the part of the guest, who in short order devoured the bread, and seemed to want more. Finally, the husband revealed what he had kept hidden until then, explaining that they had just entered a period of famine, and that was why the guest had not been aware of the presence of goat hairs in the bread. For, in times of famine, everything changed its taste, became agreeable to the palate, as long as the mouth had something to chew on, as long as it did not remain empty. The palate, the body, we were told, knew what was coming before the man himself was aware of it.

The village was poor in general, but among the poor there were always those who were poorer still. Our lands did not escape this rule. During famines, the poorest were affected more than the poor who had a bit in reserve, a few pots with yesterday’s leftovers or what remained from the previous winter. Things were more complicated for those who had no reserves at all. The story of the family that had traded a field for a meal was well known. The descendants of the relatively rich family in the village who had taken advantage of the situation were still looked on askance because of this exchange predicated on hunger. But such disapproval had not returned the field to its former owners.

And so the poorest were the most affected. They had no land to swap for food every time they were hungry. And if they did, they would not have been fed for long. The poorest did not have many fields, either.

One of those families, which had only one vineyard on land not conducive to agriculture, poorly positioned in relation to the sun and not well endowed with grapes, was constantly struggling with poverty, even in normal times. Father, mother, three boys, and two girls, they tried to make do by labouring in the fields of others. They were destitute but joyful, and working for others was not joyful. They avoided it when they could. But a task refused, a job disdained, had to be replaced by another that would bring in a little sustenance. And in this respect there was not much choice on our heights. One worked the vine, the field, and the forest, or took care of the goats and the animals of those who were busy with those three.

They could not work the fields, because they had none, apart from the vineyard rich in leaves but poor in grapes. The share of wood each could cut in the forest was limited. With unremitting overuse, the forest would soon be depleted, what with the need for firewood and wood to sell in town. And so the poor soon resorted to theft. But theft was difficult, because logs are heavy to transport, even in order to sell. Most important, such a theft was badly viewed. Trees, warming us, nourishing the animals, bringing in money when sold, were what kept the village going. You didn’t cut a tree without good reason, and you didn’t cut just any tree. You had to be sure young trees would replace the old before disturbing any part of the forest. And you didn’t touch the vines, didn’t damage the vines of others. Trees and vine stocks took precedence over goats. The branches of one, the fruit of the other, allowed a certain latitude, but their bodies had to remain intact. And so one had to avail oneself with moderation, with a smile, of what belonged to others, choosing what was within reach and edible on the spot. A light-hearted theft. Not always so for its victim. It only became a subject for gaiety later, when all that remained of the theft was the exploit, the good-natured side of it that could make people laugh when it was recounted with art and tact. Once the theft had aged a bit, the thieves were the first to turn it into a story and make people laugh at their misdeeds.

They told us about their thefts of grapes, of a chicken, of a kid, even of a goat, as if they were legends. About the goat a father had stolen in a nearby village, for instance, which he had led to slaughter in our village, only to return and hide the goat’s head under a pile of branches in the first village, the site of the theft. Getting up in the morning he was aghast to find the goat’s head under a pile of branches in front of his own house. Unable to hide his astonishment, he gave himself away, saying, “But just last night I left it under branches in your village! How could you come back and leave it here?” The goat’s head had made the return trip thanks to the spite of a villager who had seen the ruse and taken the trouble to follow the thief from one village to the other and expose him in the light of day, in full view of all the inhabitants. But even at the time the story had caused more hilarity than resentment. The villagers made reference to this goat’s head whenever they wanted to express their surprise at being faced with a situation that was hard to believe.

Thefts might well repeat themselves from father to son, but when there was no spring, they said, you couldn’t turn the mill with the water you fetched. Thefts had their limits; they perhaps helped one to survive in normal times, but they had nothing to offer during a famine, when all kept careful watch over their bits of bread, their fistfuls of salt. You had to try another way. But what could you invent when privation, famine, were everywhere?

There was also a saying, “Better to have a full belly, even i

f it’s the bark of a tree, than to have it empty.” Perhaps that is what one did when there was no other recourse? We didn’t know how the poor held on during difficult times, but they did. They managed to get through the winter and make it to spring along with the others. In any case, miracles didn’t have to draw attention to themselves. They could take place in the obscurity of a hovel and still be miracles.

Each fresh shoot glimpsed, each new leaf that appeared, was an invitation to celebrate. With the return of spring, the father sent his boys and girls out to “graze” in a nature that was just beginning to show itself. It threw off its covering, and laid itself open to all. The family’s winter table could now be moved out into the fields. The famine was over, and one sought nourishment in nature. Even in normal times, was the family not known to have green stools during the first days of spring?

And so there was a hunt for greenery through the fields, in the woods and the forest. “Herbs or leaves, everything you find that’s green, name it and eat it,” advised the father. Another expression that went down in the annals of the village. What was important was to know what one ate, to name what one ate. Everything changed its nature, became known and edible as if by magic, once it was named. Had not the Creator done as much with the first man when he presented him to the angels and the djinns? Had he not taught him the names of things, while the other creatures were deprived of this knowledge? And was it not man’s knowledge of these things, they reminded us, that had confounded some of the djinns? The father may not have been able to teach us the names of things, but he urged the children to name the herbs and in that way to save themselves from famine. And the herbs once named, the famine was swept away until the following winter, if the fields and the forest had enough greenery.

But in waiting for spring to return, whether preceded by famine or not – and aside from whatever miracles might manifest themselves in one tiny dwelling or another – man, along with other living things that looked forward to nature’s awakening, knew his share of winter and of hunger.

And he who was hungry inspired fear. He inspired fear through his hunger, because hunger was a harbinger of death. It was death made visible. As if air had become scarce and the fire had gone out, to leave us waiting for death to arrive. That was a crack, a flaw in the wheel that made worlds and life turn.

The starving man inspired fear through his eyes, his cheeks, his mouth, all of which added hollows to the hollow in the belly, opening wells of fear in the gaze of those who had so far escaped hunger. The starving man inspired fear through his capacity to wait for one knew not what. For a pail of water to be transformed into a pail of honey, for a pile of earth to be transformed into a pile of wheat, a pile of flour. He inspired fear through his patience, where perhaps there germinated the seeds of thefts to come. He inspired fear through his teeth, which at any moment might sink themselves into our morsel of food, if not our flesh. Those who were starving inspired fear in those who still had something to eat for the time being. With their eyes fixed on this emptiness, their empty table yawned open like an abyss before those who had eaten their fill, or barely, at their tables well laid, or barely. An abyss that could at any moment swallow up their meagre sustenance and leave them with only this waiting, this emptiness.

And those who were starving inspired fear in each other, just as they inspired fear in those who wanted to keep their provisions out of reach of their hunger. Just so did the cat and the dog, the dog and the wolf, the wolf and the snake, the snake and the chicken inspire fear in each other with their hunger, and feared the hunger of the other. And so the faintest odour of food unleashed flight, anxiety, and fear in the night. And that is how the cemetery in front of our house, the end point of death and hunger, became the place that inspired the greatest nocturnal fear, especially after a burial. Fear of the fresh meat that could appease the craving of an army of the hungry, that could calm them for a time in their flight. For there was no lack of stories about strange beasts that came nightly to unearth freshly buried corpses. Corpses that the earth, as famished as the rest, wanted to keep for itself. But its appetite was an appetite for all seasons. It was patient, it could wait because everything returned to it, and so it let go of what had been lowered into it. And there was no dearth of stories about this beast that, according to descriptions, was part wolf, part bear, and part man, stories that added to hunger a fear of the uncertain, of the unknown. For we could not have imagined how afraid we would have been of this thing with the blurred face, this faceless thing, if we had come face to face with it.

No one had seen the beast in question. We knew about it from hearsay: a few words from a single source, embroidered with details supplied by the imaginations of those who passed them on. No one had seen it other than a curious villager who, we were told, had hoped to surprise and unmask the beast everyone talked about without having laid eyes on it. But even that went back a long way. Accounts and descriptions were just memories blurred by time.

Since it was said that this strange beast visited cemeteries on the night of a fresh burial, and since one could learn nothing from a corpse, whether it stayed in its grave or was unearthed, the villager wanted to confirm the rumours on his own, and decided to play at being dead. Then things would be clear. One day he went and dug a grave and lay down in it at dusk to await the beast. When it was totally dark, he heard footsteps approaching. The beast had found him, had smelled his flesh in the cemetery. It had its limitations and could not distinguish live flesh from dead meat. Either that, or it didn’t care. Flesh was flesh after all, and it wasn’t going to be fussy. And it certainly was not alone in paying little heed to this distinction. Its den or hiding place could not have been far off for it to put in an appearance after every burial, but it must have been well hidden for no one to have yet seen it in the light of day. Hidden near the cemetery, which, however, did not offer many options to someone wanting to stay out of sight. We, who knew the cemetery’s perimeter, had no hiding place where we might take refuge in case of need. But the creature was there, true to its reputation, ferreting about with its nose, circling the grave to be sure it was the only guest at the feast. Pausing from time to time, still ferreting, coming closer and closer.

The false corpse stopped breathing when it sensed the beast at the edge of the grave. The beast dropped down, snuffling to be sure of its prey, and began, with its paws and its mouth, to haul the man out of the grave. During all this time the corpse had aroused no suspicions, letting himself be manipulated like a true cadaver. The beast pulled him out of the grave, hoisted him onto a stone to raise him to its height, threw the presumed corpse over its shoulder, and set off, perhaps towards its den. There was something human, the man said, in the way the beast had pulled him out of the grave, had lifted him onto the stone, and had loaded him onto its back. After they’d gone a certain distance, fear got the best of the villager. He didn’t want to take any more chances. As the beast plodded on, he started kicking at it, treating it like a mount. Taken by surprise, the beast gave a start, heaved him a good distance, ran a few metres, and keeled over. And was already dead when the man, back on his feet, went to look at it.

We were also told about a young woman who had seen it from behind and had at first taken it for human. She had been delayed in a neighbouring village and was returning to her own, not far from ours. Having left at dusk, she spotted a silhouette walking ahead of her. Not wanting to walk alone, she called out to it so it would slow down and she would be able to join it. The silhouette carried on without answering her call, as if it were deaf or hadn’t heard her. Annoyed, she decided to catch up to it and surprise it. She increased her speed without making much noise. As she approached, she saw that the silhouette was carrying a white sack on its back. When she got level with it, she pulled on its burden and asked, “Where are you going? What you’re carrying must be heavy!” To the woman’s astonishment, the beast threw down its load and fled into the darkness. Now she was filled with fear, and frozen in place. Once the fea

r and shock had passed, she bent over the load and saw that it was a corpse that had just been dug up. She returned to the village to report what she had seen, so the villagers could reclaim their dead. And they buried it a second time.

A silhouette with a corpse on its back and a flight into the darkening night. That is what she had seen of this strange beast. She didn’t know whether the beast was erect or on all fours; nor could she say how it held its load on its back. When carrying the corpse it seemed upright, but when scurrying into the darkness, it looked to be on all fours.

The descriptions we had of it came from a trick played on the beast while it was trying to lay hands on what would keep it alive for a while in its hiding place, and from an untimely encounter with a fellow traveller who disturbed it in its work. And ever since, even though no one had seen any beasts of that sort, and even if there had been no more talk of corpses being dug up, the beast and its legend still haunted our winter nights. Nights when, being idle, we were more vulnerable than during the day which, thanks to our games and occupations, kept such thoughts and fears at bay. Nights when, even out in the open, mysterious as ever, the beast was hidden from our eyes, while we, even within our walls, were assailed by the terror it never ceased to inspire in us.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night