- Home

- Seyhmus Dagtekin

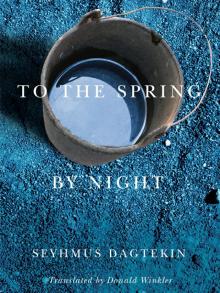

To the Spring, by Night Page 9

To the Spring, by Night Read online

Page 9

Winter passed with or without starvation and famine. It was only a parenthesis. We were warm during the day, cozy inside our houses, playing on the carpets and cushions, and when we were hungry we ate warm bread or a slow-cooked meal, or, as night fell, some dried fruit and a few cakes around the stove while listening to stories and tales told by a visiting uncle or aunt. On those occasions we didn’t complain about winter. Sheltered from outside disturbances, we could savour this period of rest, this period of calm.

It was, however, a parenthesis that froze our feet when they got wet in our plastic shoes. A parenthesis that numbed our hands, especially the tips of our fingers, which we warmed with our breath so we could feel them and keep playing in the snow all afternoon; or that burned our ears, made the ends of our noses red, then violet, after we’d been playing or tending a small herd of goats for hours in the snow outside the village, or after we’d gone with our father or big brother to gather dried oak branches for the animals still in the stable. Branches of oak that were cut during the summer and stored in a tree, high up, to be there for winter. Or the fresh branches of that tree, the evergreen oak that surrounded our houses with its little spiny leaves, green and bright, in every season.

But it was a parenthesis and winter passed. It folded its tent and beat a retreat, with all the remaining snow and cold. It retired to the mountains behind our mountains, they said, mountains as endless in expanse as in height, there to prepare for the following winter. It took away its snow and left behind the solid ground as we remembered it.

It was then that the known and the unknown changed places. With the snow and winter gone, everything became identifiable, the woods once more the woods, the terrace once more the terrace. Having grown up by one more winter, we had gained some ground on the unknown, and in the absence of snow there were no more wolf tracks on the terraces. That didn’t mean that no goat came back with its leg torn to shreds or ripped off, or failed to return with the herd. It was just that, unlike in winter, the wolf came no closer than our mountains, where it lurked around our goats. When one of them disappeared, we went to see Sofi Oussiv.

Sofi Oussiv was the most pious man in the village; he was the one who knew the most suras by heart, even if he couldn’t read or write; who never interrupted the telling of his beads and his incantations; who never left out a single prayer, and who always reserved a part of the water he brought with him from the mountain for his ablutions, whereas others only collected it to drink; who was said to be privy to things invisible and inexpressible; who at all times of the day and all times of the year, walked and talked without anxiety or haste; who never insulted his goat, or even his donkey; who when he walked abroad shared his meal with the birds and the ants; who stopped on his way when they were in trouble, returning a lost sparrow to its nest; who removed stones from the path for fear that a passerby or beast of burden might stumble; who bandaged a dove’s wounded foot with a bit of cloth cut from his shirt; who planted mulberry trees near the springs and tended them for the birds, for the joy of children, and the comfort of travellers; who arranged the springs so that everything alive could drink there in peace and enjoy the cool and the shade that surrounded them.

He was the only one in the village no one had ever heard raise his voice or shout. The only one who, whatever the situation, never cursed; who extended charity and compassion to the person before him, even in the face of hostility.

And the verses, in order for them to have their beneficent effect, had to be recited in a voice free of the baser impulses in this world below, the grownups said, a voice that commanded the respect even of one’s enemies. And so we went to the most pious man in the village, respected as such by the four corners of the village, to have him recite the verses that would, by night, lock up the jaws of the wolf. He whose animal was lost went to him with a pocket knife and gave it to him. Sofi Oussiv began to recite:

In the name of Allah,

the Beneficent, the Merciful

I swear by the sun and its brightness,

And the moon when it follows the sun,

And the day when it reveals it,

And the night when it draws a veil over it,

And the heaven and Him Who made it,

And the earth and Him Who extended it,

And the soul and Him Who made it perfect,

…

That as for him who gives alms and fears God,

And believes in the best,

We will grant him an easy end.

But as for him who is niggardly, and longs for wealth,

And calls the good a lie,

We will turn his easy life into a difficult one …

Allah in his greatness is truthful.

The recital finished, Sofi Oussiv breathed three times on the blade and closed the knife: “O Great One, as I close the blade of this knife, so in Your Goodness, keep shut the jaws of the wolf to protect the lost beast of Your poor servant.” He gave the knife back to the supplicant, for him to keep it closed all night. The supplicant went back to his house with the knife in his pocket, and hope in his heart.

Sometimes the animal was recovered safe and sound, in which case the knife had been kept well closed. Sometimes only its remains were found, and so the knife must have been opened by accident. In that case what ought to have been eaten was eaten, what ought to have disappeared had disappeared, what ought to have died had died. We knew that the verses could not do away with the wolf. That the verses were there for the wolves as well as for man. But that we could try to protect ourselves from the wolf’s hunger, if only through the verses, not forgetting that the wolf also had his verses in his language. And that the wolf’s incantation could sometimes prevail over the recitation of man.

The grownups told us that animals were most often closer to the spirit of the verses than man. They said that animals, by nature, could only obey him who rules, while man, with the possibilities that were open to him, could turn away and distance himself from this spirit. Which made man more worthy than the animals when he remained true to the spirit and turned his back on the transgressions available to him.

Knowing that animals recited verses, each in its own language, brought us closer to them. Perhaps not to the wolf, always an object of terror, envied, admired, and feared all at once, but to the other animals, and especially the birds when they began to sing. Birds whose chirping brought us closer to our brothers and sisters in the cradle, who gave us big smiles when we imitated birdsongs for them. We replied to birds with bits of verses we knew by heart, trying to answer their calls. We were happy when an exchange took place. Their peeping made the sound of the verses more pleasant. But we could not make out what the dogs were reciting when they ran through the streets of the village, nor the wolves when they made us afraid with their tracks in the snow and the marks of their teeth on the legs of the goats. Every verse is full of compassion, they said, but there was also the wrath of the verses against everything infamous. But then, why was the wrath of the dog and the wolf directed at us and at the goat when we and the goat were deserving of compassion? There were things we would know later, when we were bigger, we were told. And so we learned patience, even in fear. Patience nurtured both compassion and wrath. There was wrath that was only compassion, and compassion that was only infamy in disguise. The way things appeared did not always reflect the truth. We had to gravitate toward the true nature of things, toward their truth, they advised us. “Lord, show us the truth of each thing,” prayed the grownups. But how to expect the true nature of a bite to be revealed to us, when the goat was bitten and we were afraid of the dog?

I had kept the knife tightly shut in my pocket when my father sent me to Sofi Oussev, to ask him to recite verses for our lost goat. I loved the goats because of their gentleness, because of the softness of their gaze. I didn’t want anything bad to happen to them. Even if I sometimes made them unhappy by hitting them with a stick, because a goat when it wants something is very stubborn, that is known, and a child ca

n and must be more stubborn than the goats if he wants to tend them. It is perhaps for that reason that the grownups entrust them to us, not themselves being patient and stubborn enough to deal with them. But I didn’t have anything against the goats as long as they weren’t making me crazy, as long as I wasn’t going to be reprimanded by an uncle, or by my father on my return, because they had done damage to someone’s fruit tree or someone else’s wheat field.

Our house was at the east end of the village, and depending how they arrived, our goats were either the first to return when the herd came from the east, or the last when the herd came from the west. That day they came from the west, with the last glow of the sun behind them. They took their time getting through the village to the house, especially the curious ones who, before being closed in for the night, wanted to see what there was in every stable along the way, reluctant to leave any of them behind. Realizing that we were missing one of those curious goats, we went to see if it was perhaps dawdling somewhere as usual, mingling with the goats in a stable that was well stocked. We went all around the village without finding the goat. It was getting dark, and clearly the goat had not been delayed by curiosity; it must have wandered off far from the village, since the shepherd hadn’t noticed it on the way back. As soon as we were sure it was missing, my father called me and handed me his knife. I took the knife and ran to request the prayer for the wolf, while a big brother went looking for the goat with a shepherd, retracing the path of the herd.

Sofi Oussev was coming to the end of his evening prayer when I arrived. He performed his last genuflections, recited his prayers in a sitting position, acknowledged the angels and humans on either side. He ended with invocations and recitations, and then asked the reason for my visit and enquired after my father.

The dinner plate was set down near the stove. He faced the stove, in the position he assumed to eat: his left leg bent, supporting the body, the right knee raised, held against the stomach. It was different from most men in the village, who sat cross-legged to eat. This position, which Sofi Oussiv had learned from the wise men he had met, pressed on the stomach so that you could not fill it too much. The wise men had warned against excess in three things, we were later to learn. Too much food, because it weighed a man down and bent him under the burden of his body; too much speech, because it numbed the mind and turned one away from meditation; and too much sleep, because it made a man lazy and wasted his most precious possession, time – because sleep, too much sleep, shortened the time that might be spent on prayer and learning. Time was the greatest treasure given to man as he passed across this earth. This journey here below was for the trial of the soul, and it was the body that bore the soul upon that journey. Everything counted, both sleep and waking, and no waste was allowed.

God was a hidden treasure, they said. He wanted to be known, and created the soul, which had the capacity to know him. Once it was created, he brought the soul before him to contemplate the treasure he was, as one would set before a friend, as a gift, what was most dear to oneself, and most secret. All souls lived in this infinite love, lived in contemplation.

One day, god addressed the assembly of souls and asked them: “Do you see me as a Friend?” The assembly replied: “Of course we see you as a Friend.” God said to them: “Then I am going to send you away to see if you are sincere, to see if you will be able not to forget.” That, we were told, is how the souls were scattered, how they were exiled far from the presence of the Friend, and were subjected in this life, in this world, to the trial of love beset by absence.

In preparation for this trial, flesh was bestowed on the soul as an envelope and as a carrier. The soul was implanted within the envelope. And god ordered it down to earth to put its vow of love to the test. That is why we were told that god’s house on earth was within man. Neither the skies nor the earth could welcome god into their abode; he could only find refuge in the heart of man. His infinite being could only be at home in the vastness of this heart he had forged for it as a dwelling place. The soul’s domicile during this journey was also god’s dwelling place in the midst of his creation, they told us. And we had to keep such a place pristine; we had to keep it accessible. Those who wanted to harbour this Friend in their house had to maintain it in the best state possible. Those who wanted to welcome the Friend into their home had to be vigilant and not become forgetful. This heart must not be tainted by evil, even in thought; it must not be made unsuitable as a dwelling place for the Friend by the slightest bit of forgetting.

There is one goal on this journey, we were told: to hold fast to the memory of the Friend and of love. This journey through the world, this trial of absence, must be completed without many mishaps or much forgetting, if one is to fulfil one’s destiny by returning to the point of departure. If one is to set eyes once more on the Friend’s face, to gaze upon it, to be in his presence, in his love’s secret heart.

There were many chances to forget along the way. Every piece of finery, every beautiful thing here below could be a sign, a reminder of that first beauty granted the human eye, but it could also become a veil if man’s heart stopped short at the surface of beauty and took it for the goal. A reminder could become a source of distraction. Only through watchfulness could the heart penetrate these veils, these occasions for forgetfulness, and turn them into lanterns that would light its passage. But the carrier, the bearer, the soul’s mount, needed sustenance, needed strength to serve the soul in the course of its journey, in its trial of absence, in order that the body, they told us, not be a prison for the heart nor the heart a veil for the soul. Because in forgetting, what ought to induce watchfulness could become a well of sleep.

To negotiate the route successfully you had to exercise moderation in caring for the mount. There was no room for indulgence or for privation. One was as harmful as the other, they told us. Caring for one’s needs ought not to be the principal preoccupation of the soul, ought not to veil its light and make it stray from the path of the trial. Privation ought not to slow one’s progress. And one ought to be moderate in all things so that the mount will remain nimble, and so that its heaviness will not hobble the lightness of the soul, not weigh the journey down. So we were told.

And so Sofi Oussiv sat in his preferred position, a serene smile on his face. I held the knife out to him, saying I had come because of our lost goat. He opened the knife, read the verses, breathed on the blade, asked mercy for the creatures, closed the knife up, and gave it back to me: “Everything comes from god, nothing is done that is not his will. Keep this knife closed until tomorrow at noon. After that, open it so the wolf will no longer suffer. Because if the verses are recited well, and the incantation accepted, he can eat nothing as long as the knife is closed. If the goat had lagged behind, the shepherd would already have brought it back. If it was destined for the wolves, it will be eaten sooner or later.” He invited me to share his meal. But one must not accept an invitation when one’s parents are not present; one must not occupy the house of one’s host longer than necessary. I took the knife, put it in my pocket, and ran home holding it tightly in my hand in order to keep the wolf’s jaws shut.

Sometimes it was not the right knife, or it was not the right person who brought the knife, and the wolf devoured the goat. At other times one had become aware too late of the goat’s disappearance, and the wolf had eaten it before the recitation. Or the wolf itself had pronounced such an invocation that the On High declared the recitation and the verses void, and freed up the wolf’s jaws so that the goat might fulfil its destiny. So that the round of creation might continue, that the earth be covered with grass, that the grass nourish the goat, that the goat absorb our fear and deposit it in the entrails of the wolf. So that the wolf, in turn, leave it in its tracks in the snow, and live in dread of man, in dread of the hunter following the tracks. We never escaped unscathed from a fear inflicted on another, they told us; we always bore within us, somewhere, traces of the claws that had been planted in the flesh of the other.

When a goat came back bitten, torn to pieces, we went to examine the bite, to inspect the marks the wolf left on the goat, marks much more visible and unsettling than its tracks on our terraces in winter. We went to see the fear of the goat, which was to some degree our fear. If it had been consumed, we went to hear the accounts of those who had seen the goat’s remains, to learn how it had been eaten, and where exactly its skin had been separated from its body, thus situating its fear and its death within the geography, for the most part imaginary, that we had of the village’s surroundings, a geography that we had to domesticate bit by bit, from day to day, but which we still considered to be the domain of the wolf.

The day after the prayer at Sofi Oussiv’s, our goat came back with its hind leg torn open. Those in the village with the necessary skills all came together. They warmed oil and dressed the wound. They grilled salt and smeared it over the wound. They found animal bones, burned them in the fire, ground them up and covered the wound with them. They brought goat hair to spread over the wound. They wrapped everything in a cloth. After ten days our goat’s leg was crawling with worms. My father cut its throat and carried it far from the village to throw it to the wolves, from which we had perhaps wrested it, thanks to the prayer, when they were already gnawing at it – to the wolves and to their brothers, the dogs. Our goat was shared out among dogs and wolves. Three days later, when we passed by that place again, all that was left were a few bones and pieces of hardened skin with hair attached.

Those were times when the wolf devoured the goat and its fear, and the fear left the wolf’s entrails to lodge in ours. The grownups said that the goat lived with this fear in its gut, that it never forgot it except under the shears when we clipped its hair, and under the knife when we slashed its throat. Two moments when the fear of iron was more immediate than the fear of teeth. Two moments when the presence of man was more threatening than the ferocity of the wolf. Man, who protected it from the wolf, the better to slip it under the shears, and later the knife. All the rest of the time it was haunted by this fear. And it had to pass a little of it on to us when it looked up at us with its liquid eyes.

To the Spring, by Night

To the Spring, by Night